It happens with such regularity you could set your watch to it.

Sometime right around mid-summer, usually right before conference media day season during a lull on the football calendar between early-summer recruiting visits and preseason camp, it will appear. It takes a different form every year, and it may or may not be particularly loud depending on what’s happening in the rest of the news cycle, but it always comes around sooner or later.

It’s always a question, asked into the slowly setting sun, echoing in the stillness of a midsummer evening. The question always goes unanswered, but it is nonetheless always asked.

“What would make Notre Dame join a conference?”

Yes, Notre Dame’s persistent refusal to play in a college football conference is apparently so maddening to the rest of the country that we must revisit the topic on an annual basis. It is the most evergreen of offseason topics. It’s basically college football’s version of the Iowa caucuses.

Over time, I’ve actually grown quite fond of this little dance — rather than being irritated at having to explain independence once again, I am actually a bit tickled whenever someone trots out the “join a conference!” bit. Living this rent free in people’s heads is quite delightful, actually! It’s deeply funny when a college football event that has nothing to do with Notre Dame happens, and an immediate reaction is “how will this affect Notre Dame’s independence?” What did we do to deserve such celebrity status? Careful, we might start blushing!

My personal favorite gloss on this topic, though, is the inevitable array of “reasonable” or “common sense” schemes of college football conferences that lump Notre Dame here or there based on what other people think makes the most sense for the Irish. Ignoring for a moment that college football’s basic appeal is that it makes no damn sense at all, why exactly pundits and fans feel as though they have a better idea of what suits a particular school, its team, and its fanbase than said school, team, and fanbase is beyond me. Sure, Notre Dame’s campus is situated almost exactly in the center of the Big Ten’s geographic footprint, but that’s about as good an argument for league membership as pointing out that the Irish wear blue jerseys.

These outlines of what a “sensible” conference system might look like universally miss the forest for the trees. Namely, they all take the existence of some league structure as a given. There must always be conferences in these imagined worlds. These artificial constructions have become so enmeshed in the national fabric of college football it is apparently impossible for fans and media members to imagine the sport without them.

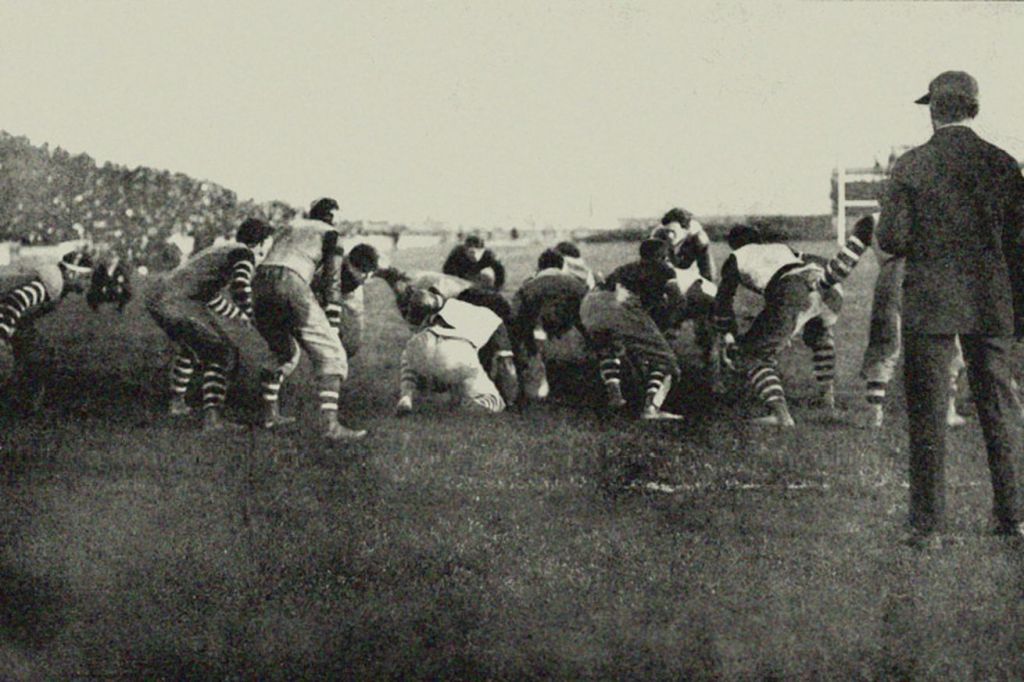

Of course, conferences are almost as old as the sport itself — but so are independents. For most of college football history, there were several national powers that competed as independents — other than Notre Dame, Penn State, Miami, Florida State, and Army have all won national titles as independent programs. No, a careful examination of the history of major conferences shows that many of them actually aren’t bound by anything in particular, and most have rarely served the original purpose for which they were founded. The Big Ten, formed to regulate the nascent and chaotic college sports scene, has now arguably propelled the sport back into chaos further than any other league. The ACC, primarily known as a power basketball conference, was founded to preserve postseason football access. And in perhaps the most ironic story, the Ivy League was founded by a group of schools that didn’t want their athletic programs to overshadow their academics. Now these schools are almost exclusively known through their athletic affiliation.

The nature of the college athletic conference has never been static. The founders of most Division I conferences wouldn’t recognize their leagues in their present form. And now, as major college football teams once again engage in a breakneck game of musical chairs desperate to find a league home, anything resembling a traditional conference structure seems to be close to extinction. Conferences look increasingly like they’re not only unnecessary for big time college football to thrive, but actually harmful to it.

So why hold on to the concept at all? Why have conferences?

What would college football look like if we just… didn’t have conferences? What if every school was like Notre Dame, able to do as it pleases without its conference affiliation tying it to a specific group of schools? Heck, given the hefty revenue haircut Notre Dame takes by remaining independent, the school must clearly enjoy independent life. I argue this is with good reason. If you ask me, college football looks a heck of a lot better if we just ditch the concept of these things entirely.

What if what’s wrong with modern college football are conferences?

Let’s start with a rejoinder to the annual parade of pro-conference offseason columns. Rather than asking what would make Notre Dame join a conference, let’s take a moment to recount why Notre Dame has resisted the overtures of every conference suitor since it started playing football over 135 years ago.

It’s funny how in most other contexts in American culture independence is celebrated, but when applied to Notre Dame football, it’s derided. We celebrate our eighteenth birthdays as a major step towards becoming independent. Financial independence is something to strive for. An independent mom-and-pop store? Better than its corporate chain alternative. Independent movies? Not everyone’s cup of tea, granted, but generally well thought of. Notre Dame’s football independence? Horribly inconvenient and a sign of tremendous arrogance.

The reasons often given for Notre Dame’s independence range from the uninformed (“they make more money as an independent” — false) to the exhausting (“it lets them play a weaker schedule” — no one made us schedule Ohio State and USC this year) to the just plain silly (“they just want to tell everyone else what to do!” — if this were the case we’d’ve joined the MAC years ago). These are all off base.

Notre Dame is independent because it has no reason not to be.

When discussing conferences, college football fans often sound like they’re hawking crypto. They will extole the benefits of playing in a league, yet seem unable to articulate what precisely these are. Usually there’s a dollar figure quoted, and an admonition that life would be so much better and simpler if everyone just agreed to this concept. But why precisely this might be is unclear. If life in a conference is so grand and so much better than life outside of one, then why do you need to expend this much energy on convincing us to join one? Shouldn’t the benefits be obvious?

As an independent, Notre Dame gets to set its own schedule. It can negotiate for itself in media contracts and in rules and management committees and isn’t beholden to the edicts of a commissioner. It has no arbitrary rules against in-league transfers or a need to watch what it says at conference media days. In fact, rather than bother with media days, Notre Dame can do literally anything else it chooses with its time. Just because your school chose not to be able to do these things, does not mean that we should give up them up. As long as Notre Dame can function as an independent, it should. Why join a league?

The fact that most teams are in conferences does not entail that this is somehow the default state for a college football program to be in. In fact, the opposite is true.

Notre Dame has no need to justify independence to you. You need to justify conference affiliation to us.

So let’s take a look at the modern college football conference.

If you think about it, college football conferences are basically communism. Somehow, we’ve arrived at a place where the most American of sports is largely run by institutions that look like they emerged from behind the Iron Curtain.

Perhaps the most obvious way this is true is how leagues distribute revenue. At a base level, league members recieve an equal share of revenue from income sources like media deals. This is the opposite of meritocracy. Indiana and Rutgers earning the same amount for failing to make a bowl game as M***igan does for making the playoff is nothing if not wealth redistribution.

Scheduling, meanwhile, is centrally planned. The conference’s top official (one might say its “premier” official) wields a considerable amount of power despite not being accountable to the people most directly impacted by their decisions. Leagues are managed by complex bureaucracies who supposed administer rules in a neutral manner but either a) exhibit gross incompetence (see: Pac-12 officiating… really, any conference’s officiating) or b) carve out special favors for the rich and powerful (see: “Horns Down”).

But the most telling part of conference authoritarianism is how schools are asked to behave, and how quickly they fall in line. Schools must tote the party conference line, are required to perform particular acts of deference to media outlets with close ties to leadership, and must display the logo of the central authority at all times. Perhaps most insidiously, they often are so loyal to the collective that they will root for their enemies if it means they defeat an outsider. If the Soviets were to take over the SEC, we might hardly notice.

Is it any wonder Notre Dame wants nothing to do with these things?

I’m being a little tongue-in-cheek here, of course. Really, conferences are not all that much different than your average corporation (though that probably says more about corporations than conferences). But the broader point stands — if you had the choice between joining an institution with this kind of control over your activities and going it alone, as long as you could do the same kinds of activities and maintain a healthy standard of living on your own, wouldn’t you opt for going solo? Most people would probably rather run their own business than work for Walmart forever. And just like a large corporation, conferences exert outsized influence on how members spend their time.

To me, by far the biggest sin conferences commit is locking teams in to fixed matchups. Given the limited number of games on a college football schedule, flexibility in who you play is paramount. You have twelve games, why lock yourself in to playing Rutgers for one of them each year? To be sure, some annual matchups are important — but teams ought to have a high level of input in picking them. Heck, Notre Dame playing five pre-determined ACC games a year is already getting tiresome — can you imagine if we were in the league full-time? (For those keeping track at home, Notre Dame last lost one of these in 2017.)

This might not be a problem if conferences restricted their control to a small portion of a team’s schedule. But they control a vast majority. Anywhere from two-thirds to an ungodly three-quarters of most teams’ schedules are controlled by the conference office. From the conference side, this makes sense — these are supposed to be leagues, after all, and how are you supposed to crown a league champion after only playing four or five league games? No, for conferences to function as a league they must play a number of games that makes sense given the size of the league. But college football simply does not have enough games to support this kind of system. Don’t believe me? North Carolina and Wake Forest, two teams in the same conference, recently played a game against each other *as a part of their nonconference schedules* because they were so tired of not playing each other as a league game. How do two schools in the same state in the same league never play each other?

As a counterexample, let’s consider a sport where conferences actually work rather well — basketball. Yes, conferences still control a majority of a teams’ schedule, but there’s plenty of room leftover to make a substantial and meaningful nonconference schedule. Last year, Notre Dame women’s basketball played 28 regular season games, of which 16 were conference games. Not only is that a smaller portion of the schedule than any college football conference, it left twelve regular season games wide open. This let the Irish play traditional rival UConn, give coach Niele Ivey an exciting homecoming game in her native St. Louis, play an in-season tournament in the Bahamas, and still host and travel to multiple power conference games.

Not only does do basketball conferences support schedule flexibility, they actually make sense internally as well. Teams play at least a round-robin schedule, with rivalries highlighted usually through home-and-home series. Each game has a real effect on the conference landscape, leading to surprising games being important in a particular year (ND women’s basketball’s matchup against Duke last year, for instance, had big conference title race implications by February, even though no one had it circled on their calendar before the season.) On the other hand, a game against a conference’s weakest team is much less of a nuisance if it’s one of thirty games than one of twelve.

It also helps conference title races, you know, actually matter. When a team emerges at the top of the conference standings in basketball, there’s a much higher degree of confidence they’ve actually earned the right to be called a conference champion. In football, a team may place first without ever playing another strong team in the conference. Or, in an even more baffling scenario, the top two teams may be forced to play a game again to determine who should be called champion (here’s looking at you, Big 12). Gosh, if only there was some method of determining who was the better team; say, if the teams had played a game of football already!

I’m not even sure what a college football conference championship is supposed to mean. Really, they’re trophies that say “you did better against a subset of the league than everyone else did.” But they are far too affected by the quality of opponents each team plays, which isn’t decided by the teams. Even before winning back-to-back national titles, Georgia won the SEC East with impunity because no one else in the division was a quality opponent. And once bowl games and the playoff start, who actually won each conference is quickly forgotten. Does anyone who isn’t a Wildcats fan care or even remember that Kansas State won the Big 12 last year?

Also, can you name the last conference title race that was exciting? I can’t. A conference title race rarely makes the regular season more exciting — upsets, rivalries, and playoff chases are all more important. Last year, both LSU and Georgia had clinched an SEC title game birth by mid-November. We saw a rematch in the Pac-12, Clemson won its seventh ACC title in eight years, and Purdue played in the Big Ten championship game. Conference title games are usually superfluous, rarely exciting, and almost always result in a coronation for a team that was already clearly ahead in the standings and the estimations of the public. And yet we’re supposed to believe that winning one now somehow merits an automatic berth to the playoff? Puh-shaw.

This is the central problem with conferences when it comes to college football — they are square pegs trying to fit in round holes. Conferences don’t work in football. As currently constructed conferences are too big to allow their members any freedom or to have a championship carry any weight. Any conference that could work internally without eating up a supermajority of its members schedules would be too small to bother — championships would have even less weight. Yet, here conferences are, shaping the fabric of the sport all the same.

This mismatch between what conferences need and what college football can support has always been a problem, but it’s about to become almost comically bad. With two sixteen-team (at least!) leagues starting play in 2024, nearly half of all power conference teams will exist in leagues where the teams they won’t play in a year could fill half a schedule. What, pray tell, will the champion of the new look Big Ten have a claim to? Being better than nine or ten out of sixteen teams?

The sole bright spot for our future megaconference hellscape is the demise of divisions, a truly horrendous idea even by conference standards. In effect, slicing each conference into two mini-conferences just compounds the problems with scheduling. Now, you are stuck playing an even smaller set of opponents each year, and you may hardly ever see your opponents in the other division despite ostensibly pledging allegiance to the same league. Thus, we get such absurdities as a “nonconference” game between two teams in the same conference and a full *decade* of league membership without a visit from a conference opponent. It also hurts that most conferences feature divisions with wild competitive imbalances, such that some division have never won a league championship. Sometimes this can result in some tragicomic fun, such as the case with the ACC Coastal’s seven winners in seven years, but in none of those years did the Coastal actually win the ACC overall. So while’s that a fun note for football nerds like me, no one else cares. Mercifully, divisions seem to be on their way out.

Except! Even this is a bad idea! It will lead to more rematches that will further minimize the importance of the regular season. The usually quoted example is the possibility of an Ohio State-M***igan rematch in the Big Ten title game the following week, but there are so many others. Imagine a regular season game between Alabama and Georgia in a year in which they are clearly the two best teams in the SEC (which, hey, is probably most years!). If these two teams are going to rematch in Atlanta in a month anyway, does that game in any way matter? Time would be that game would go a long way to determining a national champion — now it determines who wears white at Mercedes-Benz Stadium.

If a conference was simply a way to simplify scheduling, that would be one thing. Rather, conferences demand near total control over their members’ schedules to an extent that hurts the sport overall. They then add on an unnecessary conference title game to this control, and suddenly conferences look very useless. There’s a difference between creating a scheduling pact and creating a league. Agreements to schedule games regularly are good — seeing the same team often helps foster rivalries, and keeping schedules focused regionally helps build passion for the sport among competing fanbases in the same geographic area. But being locked in to these matchups on an annual basis, no matter how either side feels about the game? That’s bad. Letting college football teams decide who they play each year makes the sport better.

Scheduling freedom has worked out pretty well for Notre Dame, who’s schedule always feels fresh, fun, and exciting while retaining enough familiarity and tradition to keep a consistent identity. The Irish have chosen to only lock in a quarter of its schedule each year through annual series with USC, Stanford, and Navy. The leftover flexibility has allowed Notre Dame to do awesome things like play a game in Ireland, revive old series, explore new ones, and connect with fans and alumni across the country. In fact, its pretty hard to argue the worst thing about Notre Dame’s schedule right now is the ACC affiliate games — a direct result of conference interference. Not only are the majority of these matchups deeply uninspiring (cannot wait for our next visit to Winston-Salem, lemme tell ya), blocking out five games each year required the suspension of far more meaningful games agains the likes of Michigan State and the skunkbears. Yet even with that ball-and-chain, we’re still looking forward to resuming both of these series at some point. Could we do that if we were locked into eight games a year? Seems unlikely.

There’s absolutely no need to adhere to conferences to give college football structure. The sport, and every team that plays it, would be better off without them.

So now that we’ve addressed how conferences affect the sporting product, let’s discuss the multi-billion dollar elephant in the room — TV deals.

You probably wanted to yell at me a bit when I claimed Notre Dame had no reason to join a conference. You probably thought something like “I’ll give you $10 million reasons.” And ok, sure — as college football is currently constructed, Notre Dame would make more money if it joined the Big Ten or the SEC. But why construct things this way? Are we sure that the college football powerhouses, the big brands, the Georgias and the Ohio States and the Southern Cals, aren’t actually shorting themselves by choosing to remain in a conference?

Is there any reason at all that, say, Alabama and Vanderbilt should have their financial futures tied together? The Tide and the Commodores are fundamentally different football products that are sold together. Imagine if you went to a restaurant and ordered their finest filet mignon, but were informed that it only came as a package deal with fried worms — you had to pay for both to get either. That’s essentially how conferences sell their media rights. If I’m a filet fan, why in the world am I ok with artificially inflating the market for fried worms? Heck, if I’m a worm fan why am I ok with having to pay for the steak?

Couldn’t schools like Alabama and Georgia actually make more per year if they negotiated their own media rights? Wouldn’t those rights be more valuable if they didn’t have to play Kentucky and Mississippi State every year, and could instead use those games to play the likes of USC and Clemson?

And yes, I’ll acknowledge this is a purely capitalistic argument for abolishing conferences, one I’m not entirely comfortable with. Personally, I’d like to see a fair bit less commercialization in college sports. This line of reasoning is purely to point out that schools don’t need conferences to have financial success. If you are going to treat college football purely as a business, then it makes good business sense to throw conferences out the window.

From another angle, it’s actually conferences that have contributed to commercialization. There’s been no greater driver of the hyper-inflation of wealth in college sports than the conference’s power to make TV deals on behalf of their members. There’s a reason we saw much less movement between conferences prior to the Supreme Court’s decision in NCAA v. Board of Regents of the University of Oklahoma that stripped the NCAA of the authority to determine which games were on TV — there was simply no incentive to move outside of what made the most sense on a strictly competitive and institutional basis. In fact, most movement was by schools out of conferences! But then the floodgates opened. The Big Ten added an eleventh member but kept the name. Texas killed the Southwest Conference and bolted to join a new Big 12 conference. Having won the right to negotiate television deals themselves, schools promptly surrendered that right to their leagues.

What we’ve seen since is consolidation to the fewer and more prestigious leagues, and the slow but inevitable squeezing out of those who are on the wrong side. Like any good capitalist entity, conferences gobble up any possible competition they can if left unchecked, to the detriment of the sports’ ecosystem as a whole. In fact, conferences have now completely cannibalized their original stated purpose — uniting schools in a similar geographic region and with similar characteristics into competition. There’s been an awful lot of ink spilled on the messy travel logistics between State College, PA and Los Angeles, but no one’s seemed to stop to ask what on Earth USC and Penn State are doing in a league together. And that’s not even to think of the schools that are still riding the coattails of one-hundred year-old handshakes — your Purdues and your Indianas and your Ole Misses. Proud programs, all, no doubt, but so are Stanford and Virginia Tech and Syracuse. The only difference between them is the former few happened to be within driving distance of Chicago or Atlanta. Those who happened to be in the right place at the right time due to an accident of history are benefitting at the expense of everyone else. Now, conferences are sowing the seeds of their own destruction, crushing the spirit of the sport that lifted them to prosperity in the first place.

And all this wealth has led directly to the garish facts of modern college football, like Brian Kelly earning the largest paycheck of any public employee in the state of Louisiana while LSU’s dining hall plays host to local wildlife. It has led to ostensibly nonprofit institutions acting more like Gilded Age factories than schools when it comes to athletics. All the while the athletes that are directly responsible for these billions will see precious little of that money. Don’t be fooled by all the talk of NIL and paying players — Minnesota’s Big Ten membership netted them $58.8 million dollars last year, none of which goes to NIL deals. In fact, the Gophers can cover cost attendance for their entire football team out of the Big Ten check, and still have over $50 million of it left to not share with them.

But imagine if the guardrails had stayed on somehow. What if schools had actually negotiated their own deals instead of surrendering their hard-earned rights? Notre Dame was a leader in this space, removing themselves from the group negotiations and inking a TV deal that paid the Irish what they were worth. This has led to three decades of self-sufficiency in South Bend while one-by-one, once independent peers fall and schools jump ship for a richer tomorrow at the expense of a brighter future. The Irish have prospered from independence, no doubt; but no one’s building a lazy river or a slide up here because we have more money than we know what to do with. Unfortunately, no one else followed Notre Dame’s example. They took the easy way out. They rode with their conferences.

Perhaps the most delicious irony in all of this is that there is absolutely no reason the schools actually need this money, and any attempt to justify decisions to chase it is disingenuous at best and a bald-faced lie at worst. At least when professional leagues make moves to make money, you can be sure that some of that extra cash will make its way to the people that actually play the sport. But right now in college football, schools aren’t allowed to get into bidding wars over players with any of that revenue. Still, without fail, you will hear school administrators bemoan their lack of ability to compete for titles with limited financial resources. They will complain about their inability to build the latest and greatest opulent football palace or pony up to pay a slightly above-average coach a few extra million. But of course, if the schools were not making ridiculous amounts of money, there would be no need to build lavish facilities or pay coaches lavish salaries!

Either way, if you like institutions making millions off of unpaid labor or you don’t, conferences are absolutely superfluous to the financial underpinnings of the sport. I promise you, hundreds of thousands of people will still flock to Bryant-Denny Stadium to watch the Crimson Tide on a Saturday if they aren’t playing in the Southeastern Conference. Millions more will tune in on TV. In fact, these numbers might be boosted if they’re playing an actually challenging game their fans have asked for, instead of their local community college branch right in the middle of November. And for schools a little bit lower down the food chain, like West Virginia-Pitt? Make that rivalry annual again and you’ll see two fanbases way more engaged.

If you don’t like traditional rivalries being sacrificed to make more money, blame conferences. If you don’t like coaches being paid exorbitant salaries, blame conferences. If you don’t like money being funneled to grotesque facilities instead of players, blame conferences. Heck, even if you don’t like players being paid for their labor, blame conferences.

It’s conferences that are killing the sport.

So what the hell. Let’s dream of an independent future.

Schools are empowered to schedule who they want, where they want. No more would North Carolina and Wake Forest, who share a state and a conference, have to schedule each other outside of the conference structure. No more complaining about preferential treatment, real or imagined, for the big dogs in the league. A playoff committee that can actually hold teams directly responsible for their strength of schedule, because they decided it themselves without being beholden to a century-old eight-week hold on your calendar.

This lets teams either continue or resurrect their most natural rivalries. Lord knows ND fans miss the MSU series — without being tied to playing two or three games in North Carolina every year, Notre Dame can bring back this series and other regional ones. Pitt and West Virginia can play as often as they please. No more separating in-state rivalries through arbitrary conference divisions. We wouldn’t have to worry about losing the Apple Cup or USC-Stanford. Maybe they don’t get played every year, as eyes might wander with newfound scheduling freedom, but we don’t have to worry about them never being seen again.

There could even be regional competitions played and regional trophies awarded. Nobody’s saying we can’t have regional competitions. This would strengthen one of the stated goals of conferences — giving teams some claim to regional dominance — while actually providing real excitement and an opportunity for a surprise. Picture a “Great Lakes Cup” or a “Pacific Northwest Invitational.” These could work something like college basketball invitationals, with rotating membership to keep things fresh and a fixed number of games played by each team to keep scheduling intact. Ideally, these would have a mix of traditional powers and mid-majors to give the Boise States and Central Michigans of the world a real shot at a meaningful win over the big boys. Upsets would once again be meaningful — no mulligans here, unlike conference and playoff races. Winning one of these would be a real, concrete goal that every team could work towards, unlike the nebulous value of a conference title. But, schools could totally ditch these altogether if they wanted! The whole point is that no one is making you play Illinois if you don’t want to.

This will also help stop the absurd spectacle of games being schedule twelve years ahead of time — if there’s no need to work around eight or nine conference games a year, teams can confidently schedule a year or two out without worrying about limited slots filling up. Instead of pondering if Florida will be any good in 2032, Notre Dame could schedule a trip to Gainesville at any old time. Matchups will be more exciting when you have a sense

Would this be chaotic? Yes, absolutely! It would *rule.* Unlike the destructive chaos of conference realignment, this would add a welcome, joyous burst of chaos each offseason. It’d be like NBA free agency but a thousand times better. Instead of desperately searching for insights from spring ball or following teenagers on social media for recruiting insights, we get to bask in the glory of a scheduling free for all on an annual basis. Man, I’m getting downright giddy at the thought.

And ohmygod could you *imagine* the petty arguments? “State U won’t play us because they’re too scared!” “I don’t even know who South Tech is, why would we play them?” You think intraconference sniping is fun now? Wait until two coaches get into a shouting match over which stadium they should play in like it’s 1910. Wait until two in-state rivals inevitably fail to schedule a game because they can’t agree on a kickoff time. Wait until somebody sets up what looks like a murder’s row before three starting quarterbacks transfer to other schools and the coach has to mount an impassioned defense of his schedule at a weekly press conference. It would be glorious.

And yes, inevitably, teams will try to take advantage and pad their schedule with cupcakes to waltz into a playoff spot. But now, instead of having a convenient scapegoat in the form of a league office, we know exactly who to blame for a soft schedule — the schools themselves. Sure, you can load up on directional state schools and community colleges if you want, but everyone including the playoff committee will know just how your schedule wound up that way. No more can Georgia hide behind a weak SEC East, no more wild imbalances between the schedules of two teams in the same conference. Now you can be judged, truly, for who you play.

Now, I hear what you’re saying. What’s to stop the top schools from banding together and forming a “super league” or “premier league”? Well, all the same reasons why conferences are bad — scheduling boredom, too much familiarity with the same few teams, the inevitability of a few underperformers, and just basic arrogance. The fact is, the big time programs need a few cupcake games to maintain their lofty status (and yes, I’m absolutely counting Notre Dame here — where oh where would we be without punting Boston College into the sun every few years). Plus, I think if you gave most coaches and players truth serum they’re glad they don’t have to play Clemson or Ohio State every week, no matter how fun those games are to us as fans. There’s also a little thing called antitrust law. There’s already concern about the 16-team leagues running afoul of the feds — can you imagine if the top programs all got together and agreed to play only each other?

As I suspect we’ll find in the new superconferences, the novelty of these “helmet games” will wear off quicky. Sure, the first USC-Ohio State game will generate a lot of buzz, but will the fifth generate as much? The tenth? It’s really asking a lot for this game to live up to the branding each year. Hell, Auburn-Georgia doesn’t always have a lot of juice and their states share a border. Why should we expect two teams across the country without much history to build a great series? Even in pro football, the most intense rivalries are between teams that are close to each other. Packers-Bears. Browns-Steelers. Saints-Falcons. Geography matters when it comes to building rivalry. No matter how good the games are or how petulant the teams act, trying to brute force new rivalries into existence rarely works. Washington-Wisconsin will never have the spice of Indiana-Purdue. No, in an independent future, teams will still focus on regionality and rivalry, with a few marquee opponents thrown in. The top opponents won’t — in fact can’t — just play each other.

So that’s on-field — what about off? This is probably where I’m a bit out of my depth, I’ll admit. But it’s hard to say it would be worse than what we’re about to enter into in our new conference caste system. No, abolishing conferences actually levels the playing field. The truly great programs will still stand out, of course, but we won’t arbitrarily consider Purdue better than Kansas State because the former once grouped itself with Ohio State and M***igan. Schools will operate in proportion to their athletic department prowess and their on-field success. Win, and get rewarded; lose, and suffer the consequences.

Without a doubt, there would have to be some concessions from big schools to keep the smaller programs afloat. But guess what! Teams already do this! There’s very little need or incentive for schools to schedule FCS or mid-major schools now, yet every team does so. Buy games would still exist and they’d help teams remain competitive outside of a conference structure.

And things get even better for the big players — they can stop fighting wars with their leagues for special treatment. Now, they can just do what they want. You don’t have to browbeat the rest of your league into doing what you want if there’s no league to browbeat! You would be totally free to do what’s best for you without concern for how it comports with the interests of a group of schools that have a loose affiliation with yours. I’m a little surprised Texas hasn’t figured this out already, in fact.

An all-independent future is the only one that serves the interests of richer schools without squeezing out the smaller ones. Would it be perfect? No — no structure for college football would be, that’s part of the charm — but it might the only way for the sport to retain its unique soul. It certainly looks a hell of a lot better than whatever nightmare land of cross-continental leagues we’re about to launch into.

So let’s all take a moment to dream of an independent world, one where college football teams have absolute freedom to play who they want, how often they want. No more of these ridiculous conference title games or lost rivalries. An independent world is a better world.

Of course, this being college football we’re talking about, the myriad reasons to ditch conferences altogether mean they are absolutely going to be a part of the sport forever. The basic law of college football is that if it makes sense, it won’t happen.

Notre Dame still isn’t in the Big Ten, after all.

– EC

Leave a comment